August 2013: Why women are always looking over our shoulders.

If I were a man, I might even prefer Delhi to Mumbai. I’m serious—in this city, I miss Delhi’s roads, space, parks, infrastructure, cleanliness… the works. But Delhi is a gendered experience, and, as a free-spirited woman, nothing makes the misogyny of the average North Indian man from the Cow Belt and patriarchal Punjab and Haryana worth it. When fear of rape and personal safety become overriding concerns, it shackles you; traps you in the golden cages of your cars, houses, society, familiarity; enforces the protectiveness of a male friend or relative who must escort you home after every night out; occupies some part of your brain in thoughts about safety all the time; changes your dress, your demeanour, your personality. It impacts your career: when I took over as the Editor of India’s leading décor magazine when I was 24, the learning curve was steep, the work unrelenting. I’d consistently come home past midnight in public transport—and know that, were I in Delhi, at some point my parents would have said enough, the possibilities were too dire. Even for less ambitious women from more conservative backgrounds who find self-worth and liberation in regular 9-5 jobs, Mumbai’s culture, transport and male mindset in general are way more conducive.

My friend Jordyn says that, with my personality type, I cannot live in a place where my race, gender, religion, etc are factors in my way of life, my freedom to do what I want to do, say what I want to say, go where I want to go—my freedom to be. I guess he is right, and I am destined to live my life in liberal, cosmopolitan cities. In India, Mumbai it is.

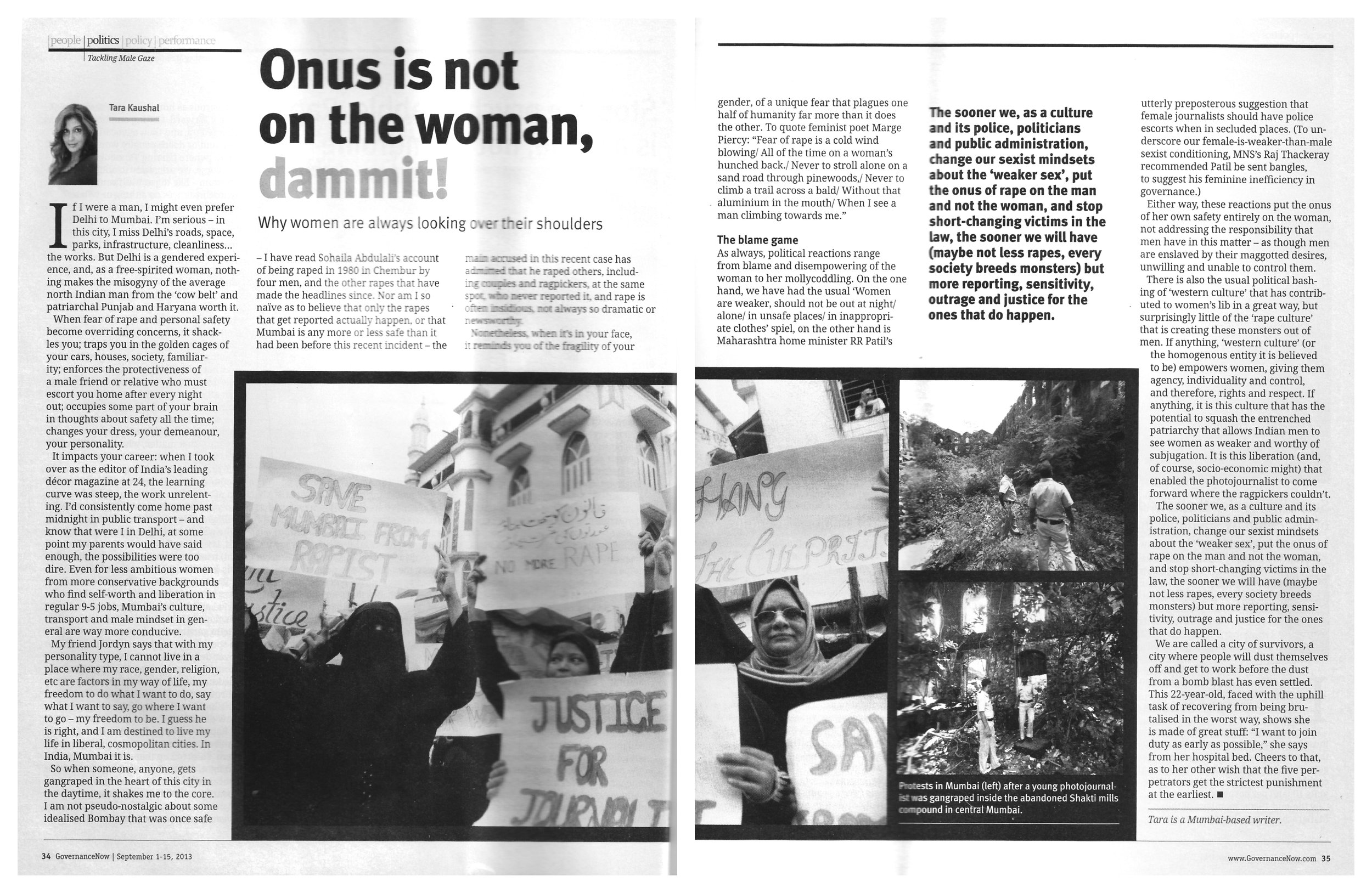

So when someone, anyone, gets gang raped in the heart of this city in the daytime, it shakes me to the core. I’m not pseudo-nostalgic about some idealised Bombay that was once safe—I have read Sohaila Abdulali’s account of being gang raped in 1980 in Chembur by four men, and the other rapes that have made the headlines since. Nor am I so naïve as to believe that only the rapes that get reported actually happen, or that Mumbai is any more or less safe than it has been before this recent incident—the main accused in this recent case has admitted that the gang raped others, including couples and rag pickers, in the same spot, who never reported it. And, besides, rape is often insidious, not always so dramatic or newsworthy. Nonetheless, when it’s in your face, it reminds you of the fragility of your gender, of a unique fear that plagues one half of humanity far more than it does the other. To quote feminist poet Marge Piercy: “Fear of rape is a cold wind blowing/ All of the time on a woman's hunched back./ Never to stroll alone on a sand road through pinewoods,/ Never to climb a trail across a bald/ Without that aluminium in the mouth/ When I see a man climbing toward me.”

The Blame Game

As always, political reactions range from blame and disempowering of the woman, to her mollycoddling. On the one hand, we’ve had the usual ‘Women are weaker, should not be out at night/alone/in unsafe places/in inappropriate clothes’ spiel, on the other hand is Home Minister RR Patil’s utterly preposterous suggestion that female journos should have police escorts when in secluded places. (To underscore our female-is-weaker-than-male sexist conditioning, MNS’s Raj Thackeray recommended Patil be sent bangles, to suggest his feminine inefficiency in governance.) Either way, these reactions put the onus of her own safety entirely on the woman, not addressing the responsibility that men have in this matter—as though men are enslaved by their maggotted desires, unwilling and unable to control them.

There is also the usual political bashing of ‘Western Culture’ that has contributed to women’s lib in a great way, but surprisingly little of the ‘rape culture’ that is creating these monsters out of men. If anything, ‘Western Culture’ (or the homogenous entity it is believed to be) empowers women, giving them agency, individuality and control, and therefore, rights and respect. If anything, it is this culture that has the potential to squash the entrenched patriarchy that allows Indian men to see women as weaker and worthy of subjugation. It is this liberation (and, of course, socioeconomic might) that enabled the photojournalist to come forward where the rag pickers couldn’t.

The sooner we, as a culture and its police, politicians and public administration, change our sexist mindsets about the ‘weaker sex’, put the onus of rape on the man and not the woman, and stop short-changing victims in the law, the sooner we will have (maybe not less rapes, every society breeds monsters) more reporting, sensitivity, outrage and justice for the ones that do happen.

We are called a city of survivors, a city where people will dust themselves off and get to work before the dust from a bomb blast has even settled. This little 22-year-old, faced with the uphill task of recovering from being brutalised in the worst way, shows she is made of great stuff: “I want to join duty as early as possible,” she says from her hospital bed. Cheers to that, and to her other wish that the five perpetrators get the strictest punishment at the earliest.

An edited version of this column appeared in Governance Now in August 2013.